29 November - 18 April 2014

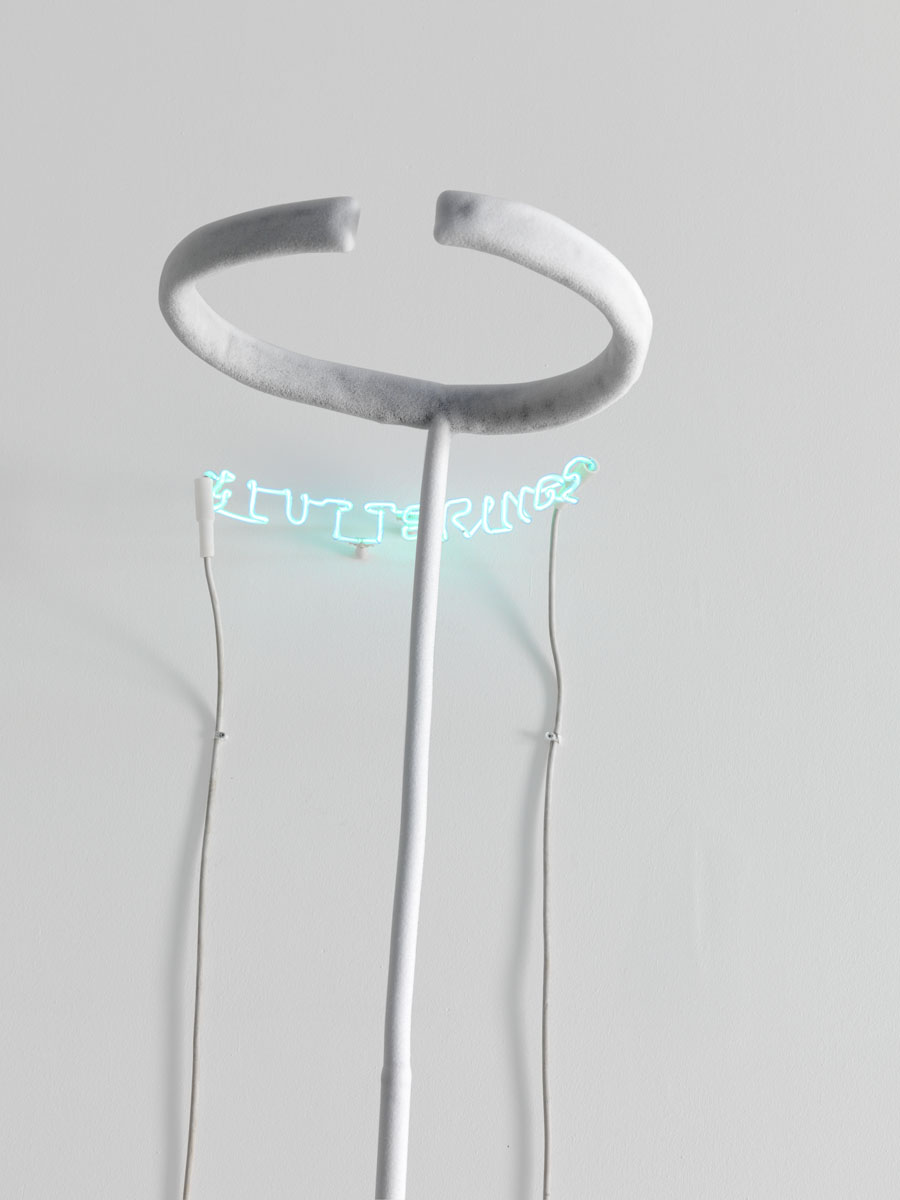

Much twentieth-century art has been characterized by an intense and eager longing for community: poetic community, a community of intents, a community of life, political community. For over a century, artists have believed they could transform the relationship between life and art, merging these two moments into a single great movement that could lead seamlessly from art to life and from life to art. And this mobilization — which has been expressed in myriad different ways, as part of the heterogeneousness of avant-garde and neo-avant-garde “movements” — required the sharing of an ideal, of a single idea affirmed and embraced by the revolution of society, not just aesthetically, but politically as well. This was, after all, the search for the identity of a figure that we tend to take for granted; an obvious figure, but one that, upon closer examination, revealed its very short history: the figure of the artist. It was not until the nineteenth century that the artist emerged as the subject of his own history, when he appeared in search of his own physiognomy, at the very moment when History was shattering every certainty of identity, under the powerful blows of a planetary nihilism characterized, as Nietzsche put it, by the twilight of the idols and the transvaluation of all values. The artist, rooted in a trade-related tradition for millennia, suddenly found himself thrown into the disturbing territory of absolute freedom that made him independent (that is, an individual called to bestow himself with his own law), and maudit, accursed, as he could no longer find his own professional connotation in the society of his time. By subtracting art from all the “servitude” it had been submitted to (of a religious, social, authoritative nature, or purely for the sake of leisure), the artist found himself having to retrace the outline of an identity, his own and that of art, which no longer knew where to look to find the reflection that could tell it where it was. The magnificent self-portraits by Fantin-Latour and, above all, his group portraits of the new generation of accursed artists was one of the first and most impressive of the symptoms. There is no need to go over the phenomenology of this identity-related research, which from the early twentieth century would lead to the definitive collapse of the great narratives of modernity; a collapse that coincided with the tearing down of the last wall capable of keeping this Weltanschauung artificially alive, and under the threat of violence: the Berlin Wall. For the whole of the twentieth century, it would be hard to find first-rate figures in this scenario, both national and international, who were free from this temptation — obviously, with poetic and political nuances of the most diverse shades and hues. Morandi himself, in the years between the two World Wars, would show a certain interest, at first in artistic terms, in the Futurist movement and, later, in political terms, in Fascism. This embarrassing biographical note indicated something that transcended an individual weakness, a weakness that the importance of the work produced over more than half a century would invite to remain silent or be of secondary importance, following a rather cloying leitmotif, according to which the greatness of a work would not be touched by the poverty of the biography. The truth of the matter is that this was a sign of the times that helps us to understand the compelling and desperate need — in some cases naive and not sufficiently thought out — which each artist had to come to terms with so as not to be reduced to his own caricature. It was necessary to understand what art could do with the endless freedom it had been able to earn in the previous century. It was a question of redefining the very concept of artistic practice, its meaning and function in society. Conversely, this also meant redefining the role of the artist, his social status, his responsibilities. Clearly, it was easier and no doubt more fascinating to answer these questions collectively. To remove oneself from the angst-ridden and claustrophobic dimension of the Me, and thus become involved and, to a certain extent, lost in the reassuring and welcoming affirmation of an Us. We now know that over the past few decades all these magnificent, progressive destinies were tragically overcome. Here and there what remains is the vestige of a monumental past, watched over by the belated guardians of a lost orthodoxy, who, while observing the desolate scenario of an amoral market devoid of ideology, except for that of profit, nostalgically lay claim to the community experiences of the past as the possible salvific ark in an era of darkest night vis-à-vis ideas and ideals. But these guardians of the past more closely resemble feral figures who, blinded by failure and by the ruins right behind them, are unaware of the fact that, even in the darkest night hours, new dawns of light are appearing, which require new eyes and new ways of seeing. What the nostalgic don’t realize is that leaving hope for the future does not mean taking refuge in the past, nor projecting oneself into a utopian future, and even less so, being totally sunk in a supposed contemporaneity. Instead, one must be untimely in today’s actuality, in this time that we — akin to those who came before us — have ended up living in. To anyone who has ever visited the apartment in via Fondazza in Bologna, or the artist’s summer home in Grizzana, it is immediately clear, glaringly so, how Giorgio Morandi, in spite of several infelicitous outbursts, lived the intimacy of a time and a space that had little, perhaps nothing, to do with his day and age. The still life — and not the unstoppable flow of historical events — was the dimension that occupied the Bolognese painter’s mind, monopolizing his gaze. For many years, infinite series of compositions of objects were used to redesign spatial balances that resembled metaphysical ones, albeit completely different from de Chirico’s Metaphysics. Morandi’s is a metaphysics of the everyday, of a sort of wonderment triggered by the most ephemeral and most commonplace materials. In many ways, Morandi’s painting calls to mind an atmosphere of humble things on the edge of History as described by Antonio Fogazzaro in Piccolo mondo antico (The Little World of the Past), or the «voce delle cose prime» (voice of primary things) by the crepuscular poet Gozzano, as well as, but in a more predictable way, the poetry of Montale. What is expressed in the artist’s still lifes — such as the wonderful one he painted in 1931, on display here — is the sense of another time with respect to that of the century, almost as if through those objects consisting of nothing, barely visible against a grey- beige background of thick brushstrokes, something appeared that transcended the flow of the events (that year, if we look at Italy alone, was the tenth anniversary of the fascist dictatorship; a great deal of importance was given to the enforcement of the Rocco criminal code; the newspapers exalted the second exhibition, in Rome, of Italian Rationalism and, from a political-military point of view, the Italian army’s colonialist conquest of the Kufra oasis in Libya was greeted enthusiastically). Morandi was on the edge of everything. He was completely absorbed by the matter of a gaze capable of capturing the essence of a bottle, a lamp. He was both tormented and felt ecstasy before those bodies that were always identical, motionless, and yet brimming over with movement, with vital élan, with transcendence in the very heart of immanence. His art is the sign of this silence imposed on the boisterous ranting of the times. And, within these poetics, the “snowfall” of 1940 features an exemplary symbolic force. A profound silence restores to the landscape its original energy. The snow is virginal, no trace of any kind, no sign of man can be seen on it. A tabula rasa devoid of the destructive violence of the avant-gardes. Only the tree branches break the vision of what persists that was man-made: the place where one lives, one’s home. It is as if the viewer has achieved a zero point, an opening before seeing, beyond where one is alone; where there is no longer any space for any of “us”, no sharing, no social identity. All that remains is the silence of a vision that is always identical and yet always new. No noise, except for the batting of one’s eyelids that can hardly believe the beauty of the world, in its endless grace. When we perceive the presence of a work by Pier Paolo Calzolari, we always have the feeling that something changes in space. Indeed, we find ourselves faced with a presence, an entity that, imperceptibly, by setting in motion all its senses and not just that of vision, completely transforms not just the viewer’s perception, but also the very confines of space and time. Calzolari imposes a change in perspective, a spatio-temporal translation. In this sense, his art is metaphorical: it takes us beyond. Metaphorà: i.e. that which leads from one dimension to another, from one form to another, from one meaning to another. A surprising metaphorical machine, Calzolari’s art transforms vision into an experience that is autre, poised between a multiplicity of senses. At bottom, Calzolari’s works open up to the senses in every way possible. If, then, when we look at works such as Natura morta (Still Life) (2006) or, even more powerful, Valori plastici C (Plastic values C) (2005), we discern a metamorphic force that transports us elsewhere, at the same time we have the feeling that this elsewhere is still here. We can see that if art has the power to help us to escape from the pure contingency, this is so it can lead us to the very heart of immanence. In plain words, the work shows us that the mystery is right here, enclosed in the material: tempera grassa with milk, wood, eggs, cotton, copper, terracotta, brass, refrigeration unit, refrigerator motor, lead. Calzolari’s metaphors do not take us “beyond” but, rather, “between”, like the etymon of the word meta. It is between things, between one thing and another, between one meaning and another, between the yearning to intervene in the world, and to take refuge in it, between activity and idleness, between art and life, that they find a homeland. Between the Acts, between one act and another in time, like virginia Woolf’s last great novel, these secular altars announce a dimension of time that is entirely outdated in respect to today. If meanings do exist, they must always remain indefinite, open, perhaps hidden or even secret. And even the small tributes experience their own life of profound postponements, of elective consonances and affinities that do not need to be clarified. The entire process reminds us of a game of correspondences of Baudlerian significance. Calzolari, like others in our century, but often with greater formal strength, shows the possibility of an ecstatic materialism, of an ecstasy of the material, of the material’s exile from itself. Neither an absurd and anachronistic return to a classical metaphysical dimension, nor a blind and arid materialism. Neither one nor the other, but in between. All of Claudio Parmiggiani’s work plays out between life and death. What exactly is that impressive Macedonia white marble structure that fills an empty room where butterflies hang upon the walls? The first image one sees is that of Beato Angelico’s Sepolcro vuoto (Empty Sepulchre); but any trace of suffering women and even less so of celestial images of the Risen Christ is gone. All that is left are traces of mute witnesses, such as these butterflies, which stay quite still, indifferent to everything around them. But perhaps, instead, it is simply a sarcophagus, like Sarcofago delle Ammazzoni (Sarcophagus of the Amazons) in which antique paintings are dissolved or, rather, transformed into patches of colour with their own life, the butterflies that now fly away, free at last. Images of a death that, despite the excruciating pain, cannot hinder metamorphosis, rebirth. Or, perhaps, it is none of these things; instead, it is an ark destined to guard the beauty of the world and, for this reason, it is left open so that each generation can add to it what is new and vital. It is an ark of alliance between the artist and beauty, between one generation and another, handed over to us thus, open, so that it will remain open. The artist is the guardian of this opening, of the need for it. Only for as long as the ark remains open will there be a chance, an infinite one, for new beauty. The artist, for Parmiggiani, is the witness to these signs addressed to an absent or future gaze, always to come. His works are images of hope destined to a castaway of time. The artist himself being a castaway, he survives his own time: he is a survivor. His survival is almost a sentence: he is sentenced to his own freedom, to the inability to escape his responsibility as a witness to what has been and what — he is conscious of this — might and will happen endless other times: love, birth, life, death. The ‘delocations’ are the traces of this unstoppable flow, of this inexorable destiny, of this tragic vision that, like Orpheus’ gaze, is forced to cause, a second time, owing to an excess of love, the death of the beloved subject: possible salvation is not what is offered here, but, rather, the possibility and the joy of the gaze, each time as if it were the last one, each time again as though it were the end of the world. The artist loves life to the point that he leaves nothing but traces of death as proof of its incommensurable beauty. And so his life, confronted with the absence of the common measure of beauty, is necessarily solitary, of a solitude that is ontological more than physical. Solitude that is happy at times, desperate at others. But each solitude encounters a limit, and this limit is another solitude. In that instant life takes place and art is made. All the rest is silence, the enigmatic silence of the artwork. The Untimely, this could be the definition that all these artists have in common, like others before them and, probably, after them. They are not given a single formal identity, nor a poetic one. Every attempt made to add them to the currents of their own time has failed. Certainly, we are reminded of Nietzsche’s visionary Untimely Considerations, and even more so of his der letzte Mensch, the Last Man, and his counterpart der Übermensch, the Superman, figures that, multiform and many-sided, have accompanied twentieth-century art and thinking. Everything in the history of the century that has just come to a close is played out around these two determinations of the human being. What’s at stake in the great politics, both cultural and social, is the definition of these two figures; the attempt to kill or resuscitate the former; to give birth to or ward off the latter. (Thomas Mann’s Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man are a dramatic and more transparent example of this titanic struggle.) What was really at stake was the definition of a new humanity and a new way of thinking, as well as a new art. The “last man”, his secluded and crepuscular survival, was already the announcement of what went beyond man, of that Übermensch that surpassed him in the form of a subject that was even more unseen and undefined, of that Humanity, in the great collective dream I mentioned at the beginning of this short essay. To dream of man beyond man; humanity that is always at the beginning, always on the verge of being born, always an infant, in a Kinderland where all confines have disappeared, a planetary one, in perpetual communication, with no centre and no periphery. This is the dream of almost all the avant-gardes. To dream of the world, to dream truer, and to enable that dream to penetrate the folds of all of life. The dream of a thing, of Marxian memory. Today, more than a hundred years after Zarathustra’s announcement, beyond the Last Man and all his dreams it seems there is no one left: only the individual, the untimely one remains. The untimely one is the personification of the laceration that took place between the Last Man and the Superman. The untimely one bears within an angst-ridden, dismembered, solitary humanity, incapable of unity and identity, but filled with wonder, inebriated with the world and with renewed marvel. Suspended, neither here nor there, a bridge hangs over nothing; a hand that traces, without seeing, the ungraspable lines of its own face — this is the fleeting portrait of the untimely one. In the undecipherable light of an endless sunset or a dawn that can hardly disappear it is hard to understand whether an ultimate Zeithild is appearing, or whether what comes after the Last Man is only a face that has been irreparably disfigured. Residue or ruin of the flâneur, the dandy, deprived of the aura that came from his idle and nonchalant search for meaning and his being «le dernier éclat d’héroïsme dans les décadences» («un Hercule sans emploi»), he has perhaps for the first time ever found the meaning of a process without a goal that coincides exactly with the process of his own action, of his making of an action, without this action ever becoming a monument. A mad production of meaning, beyond any unique meaning, any identifiable destination, any directing figure. A cosmetic meaning that is traced, flashes, appears and disappears, on the skin of the world, on the naked body of the world-image. Beyond the Last Man is the “untimely one”, with his ability to show what has never been seen before, the unconscious of the image and of the world- image. The unseen, point of arrival of appearance, the disfiguration of every hegemonic figure, the instant in which the hitherto unseen gains access to vision, it becomes vision. The untimely gaze is the blind point of this vision of the unseen. In the 1930s, like today, the ‘untimely one’ was as if suspended between the folds of his own time, from which he could not flee, but neither embrace: he embodies the hitherto unseen image of a humanity to come, always to come, via the image of a time in which all the eras are contemporary and the living and the dead return to their endless dialogue, for an entretien infini.inattuali